Social Practice Artworks

Chris Johnson

Text and images from: Art as Social Practice: Technologies for Change Published by Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Introduction

The Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York where I grew up, was once considered to be the largest ghetto in the United States. As a Black boy in the 1950s and 60s it was very easy to see that there were stark and profound choices all around me: On the one hand, Malcom X and the Nation of Islam were powerful voices of protest against an oppressive white America.

There was also the multiracial Civil Rights Movement with heroes like Martin Luther King Jr and heralds like Bob Dylan and Pete Seegar and Joan Baez and Len Chandler. These were poetic musical artists and their truths about life and American culture resonated with me in ways that I feel strongly to this day.

|

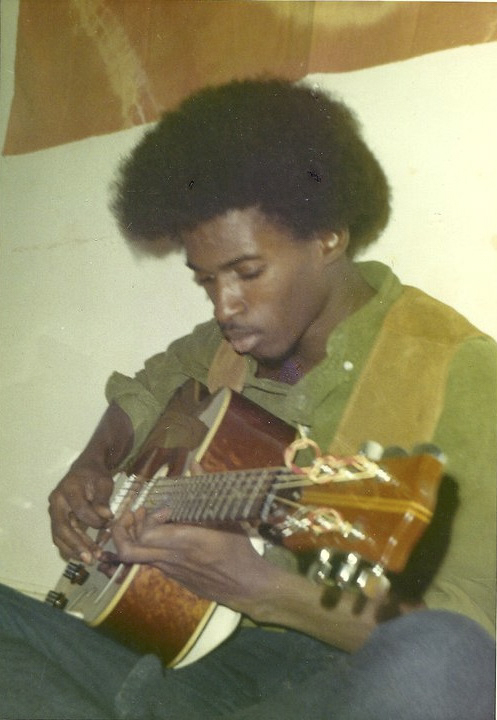

I began as a folk singer, playing guitar and trying to reflect social and political truths as I experienced them and in 1967, I moved from New York to San Francisco looking for peace and freedom. One of the first things I discovered was that I had no real talent for music. I took up fine art photography and discovered that seeing itself could be a creative process as fine art photography. I was lucky to discover a community of artists including Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams, Judy Dater and Wynn Bullock who all became dear friends and inspirations.

My artwork at that time was deeply personal. In the self-portrait triptych below I reenacted an incident where my mother punished me for playing with fire. This was done in the lighting studio at the California College of the Arts (CCA) where I had become a tenured Professor.

|

Social Practice Artworks – Beginnings

The Oakland Firestorm: Family Portrait Project

Chris Johnson and Richard Gordon, 1991

|

The Oakland Firestorm: Family Portrait Project, Chris Johnson, Richard Gordon and many great friends. 1991

In 1991 the hills of Oakland California experienced a devastating urban fire that killed 25 people and destroyed almost 3000 homes. In response to this tragedy, I discovered for the first time that portrait photography could be organized into a project that met real human needs. Together, with fellow photographer Richard Gordon, we organized The Family Portrait Project. The idea was to bring together many of our photographer friends to provide free family portraits for victims of the great Oakland Firestorm; film and processing was donated by Adolph Gassers, a local camera store. Families arrived at the lighting studio at CCA, some of them wearing new clothes that they had to buy after all of their belongings were destroyed in the fire. Many years later I ran into someone who remembered this and told me that images from this project are the oldest photographs he had of his family.

The Roof is on Fire

Suzanne Lacy, Chris Johnson and Annice Jacoby, 1993-1994

|

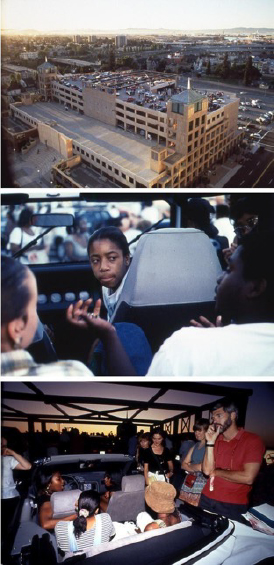

The Roof is on Fire, Top: The performance site in downtown Oakland; Middle/Bottom: young people talking in cars while audience listened.

Two events in 1994 changed the course of my creative life: A group of students from Castlemont High School in Oakland California were widely criticized for laughing at a tragic murder scene in the movie Shindler's List; and, Suzanne Lacy, the renowned pioneer in the field of socially engaged and public art, invited me to collaborate on a major performance project with the goal of helping mainstream America to better understand the thoughts and feelings of BIPOC teenagers.

Suzanne had come to CCA as the Dean of Fine Arts and I was then one of the few African American faculty available for her to work with. Fear and anger towards black and brown teens were major problems at that time. Suzanne and I began imagining how a very public event might help address these perceptions of minority youth.

There is nothing new about the idea of the creative process being used to raise public awareness of key social and political themes. Examples of highly intentional public actions being used to shape public opinion include the storming of the Bastille, the Boston Tea Party and Gandhi's Salt March.

Suzanne and I agreed that two concepts would be important for this project.

First, the young participants needed to know that they were safe and free to express themselves with their own authentic voices and honest feelings about the things that mattered most to them: personal issues and what it felt like to be feared and misunderstood by the world at large.

Secondly, we also needed to design a setting that would ensure that these teens of color would really be heard by just those members of the public who were the least inclined to take them seriously.

The result of the collaboration was The Roof is on Fire, a project that featured 220 public high school students who had unscripted and unedited conversations while sitting in 100 cars parked on a rooftop garage in downtown Oakland. Each student had a sign around their necks that read: "Shut Up and Listen" and over 1000 Oakland residents came and did just that while the young people talked freely about their lives.

The event proved to be transformative for the BIPOC teenagers who participated in the project, who, for the first time, were able to share the rich complexity of their views without being interrupted or judged. The mainly white adults, who were the audience for this work of performance art, came away with insights they could never have gained in any other way.

The Roof is on Fire aired as a one- hour documentary on the Bay Area’s local NBC affiliate, and was covered extensively on local news and nationally on CNN. Collaborating artists including Annice Jacoby, Jacques Bronson, Unique Holland and Stephanie Johnson.

Question Bridge: Black Community

|

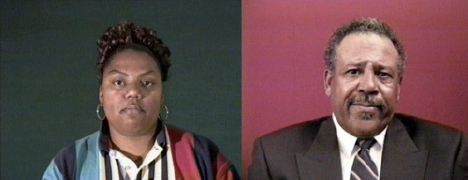

Keyona Johnson and William Gaines (from Question Bridge: Black Community 1996)

The vital thing I learned from The Roof is on Fire project was that an imaginative process can be designed that might heal painful rifts between people who, for complex reasons, are divided from one another.

This concept came to mind when I was invited to take part in Re: Public, a multimedia exhibition at the Museum for Photographic Arts in San Diego, curated by Richard Bolton. The exhibition was mounted to coincide with the 1996 Republican National Convention and the invitation to participate in the show came from my good friend Arthur Ollman, the museum's first Executive Director.

I had never worked with video before but I immediately knew of a group of people who were desperately divided from one another by historic events that I had witnessed in my own childhood:

Before the Civil Rights Fair Housing Act was passed in the 1960s, African Americans were prohibited by law from buying or renting homes outside of neighborhoods like Bed-Sty where I grew up in New York City. But, as soon as these historic laws were passed, the Black Community divided into those who, for many reasons, chose to move away from the Hood and those who needed to, or decided to stay.

The consequences of this division can be painful and costly for those on both sides of this divide and I know from my own experience that each group embodies meaningful truths that the other needs to know and understand:

Blacks living in inner-city neighborhoods need role models and resources; Blacks living away from Black communities can often feel isolated and estranged. Divisions of class, language, aspirations and geography mean that there are no natural or easy ways for a significant dialog about critical issues to happen across these boundaries.

I had seen from The Roof is on Fire that listening could become a powerful creative tool for healing. Listening is essentially a passive act of generosity that primarily works in only one direction. What I needed for this new project was a more actively generous and two-way process that would allow for those on both sides of the critical divide to express themselves and also learn from each other.

There was a moment when I realized that I might be able to use the act of asking a question as a key tool for a new project. If people on both sides felt free to ask and answer sincere questions of each other, I might be able to create a Question Bridge that would work to build understanding between them! I also thought that video might work as a way to create a safe setting for individuals on both sides to express honest and challenging questions of each other, and provide meaningful answers.

I was given 8 weeks to see if this experiment in social practice would work, and it did! The key to allowing for the final version of this project to feel as if the participants were speaking to and listening to each other was for me to direct them to look into the video camera's lens and imagine that they were speaking to someone who was Black but living a very different life from themselves.

With these simple instructions as guidelines, I was able to get African American men and women to ask questions like: "Have you given any thought to where the money for public assistance comes from, and do you care?" or "Why do you feel like you need to talk and act like a White person?" Presented with questions like these on video, I was amazed at how passionate and relevant the answers I was able to record were!

Young Black mothers were very willing to say how aware they were that Welfare comes from taxpayers but that only a small percentage of Black teenage mothers were being irresponsible in how they used this money to support their children. Middle class Black men felt free to share their strategy for success with comments like “If you hope to get ahead in mainstream America you need to be understood and respected. If that means “acting White” then so be it!”

The final, one hour video presentation feels like a challenging and strikingly honest faux conversation between Blacks from many different backgrounds and points of view.

Question Bridge: Black Community proved to be a turning point for me as an artist.

This button will take you to a short excerpt from this original Question Bridge project.

Question Bridge: Black Males

Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas - 2012

|

Top: Chris Johnson, Bayeté Ross Smith, Hank Willis Thomas Below: Question Bridge: Black Males installation

Fear and suspicion of Black men has been a universal problem in the United States since long before the killing of George Floyd and the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement. African American men are generally seen as members of a stigmatized group rather than as individuals with precious human lives.

In 2007 Hank Willis Thomas had the idea that the Question Bridge process that I had created years before, might be adapted into a major project that could be designed to address this problem. He called me to see if I would be interested in collaborating with him to recreate my Question Bridge project but with two major differences:

1) We should use Black men in America as the focus of our new project, and

2) We should not predetermine their questions.

Instead, we could simply direct them to look into the lens of our video camera and ask a question that they had always wanted to ask a Black man very different from themselves.

The men in our project asked questions that could be disarmingly personal: For example one young man in New Orleans asked “I try to be a good person but I’m surrounded by bad. I want to know what it is I can do to do better, and live peaceful, when I’m surrounded but all evil. How can I do that?”

Another man in Philadelphia asked: “Why is it so difficult for African American men to be themselves, their essential selves, and to remain who they truly are?” The answers we gathered to these questions are meaningful, not only to Black men, but also to anyone struggling to grow emotionally and spiritually.

One of our goals was to make it possible for viewers to feel as if they were gaining very personal insights into the hearts and minds of Black men who they would never encounter in their daily lives. Working with a team that included Kamal Sinclair and Bayeté Ross Smith, it took us four years to visit 11 cities across the country and record thousands of questions and answers that were edited into the final three hours version of Question Bridge: Black Males.

The success and continuing influence of this project has been a wonder to all of us on the Question Bridge team. The project has been on display in dozens of museums and other cultural venues continually for years after it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2012. The Aperture Foundation published a book based on the project’s contents and it has been acquired into the permanent collections of the Oakland Museum of California, the Harvey Gantt Museum in North Carolina and the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

Question Bridge: Black Males is also being used in schools across the country to help promote transformative conversations in classrooms on issues of racial justice and equity.

WisdomArc Time Machine

Chris Johnson and Eric Doversberger, 2013

|

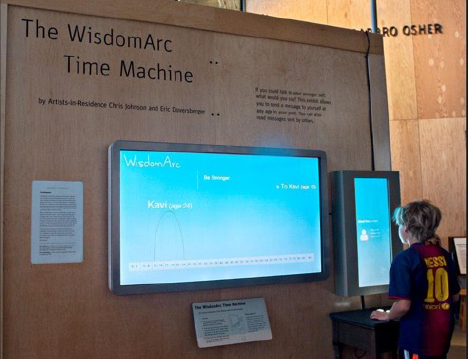

Wisdom Arc Time Machine installation at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, Chris Johnson, Eric Doversberger 2013

If you could send a message to a younger version of yourself, what would you say? With the advantage of lived experience, would you offer yourself some wise advice? Or, would you be afraid that you might change the state of your current life?

These are the questions and ideas behind an interactive project that Eric Doversberger and I created for an installation at the San Francisco Exploratorium in 2013. Eric did all of the computer programming for this project, collecting thousands of wisdom messages that are archived within the interface for all to read.

Here are some examples:

Kelly: (age 31 to age 16): "Your mom is doing the best she can with what she was given. She is sick and doesn't know better. Just love her without expectations."

Lucus: (age 22 to age 16): "Don't do drugs you will end up bad"

Paul: (age 41 to age 26): "Choose Elisabeth again and again"

(http://wisdomarcproject.appspot.com/)

The Best Way to Find a Hero Installation

Who Is Oakland Exhibition 2015

Oakland Museum of California

|

The Best Way to Find a Hero installation at the Oakland Museum, Chris Johnson 2015

In 2015 the Oakland Museum of California asked me to curate a major exhibition for their Who Is Oakland Exhibition. The goal was to create an installation based on diverse and creative impressions of Oakland.

My contribution to this show was a project called: The Best Way to Find a Hero.

For this project I created a map that was a composite of all of Oakland’s “bad” neighborhoods. I then threw darts at this map and interviewed residents selected in this way. The resulting video clips demonstrated the integrity of those living in marginalized neighborhoods.

The Oakland Fence Project

Wendy Levy, Chris Johnson and other Contributing Artists, 2016

|

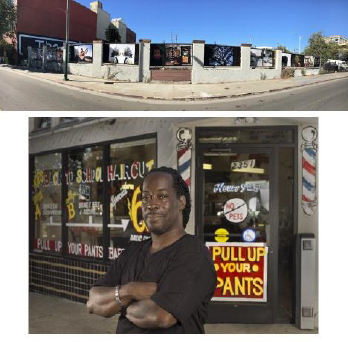

Oakland Fence Project installation, Oakland California, Wendy Levy, Chris Johnson and other artists, 2016 Below- Portrait of Tyrone Burns, Chris Johnson 2015

In 2016 I helped organize the creation of The Oakland Fence Project. I contributed a portrait of my local barber, Tyrone Burns, owner of Pull Up Your Pants barbershop in East Oakland.

This project used augmented reality that allowed viewers to use their cell phones or tablets to see an accompanying short video of Tyrone Burns telling the story of how he created the concept for the barbershop based on his desire to promote self-respect in the community through leadership and by being a positive role model for young Black men.

A Question of Faith - 2018

|

Click to see more of these images

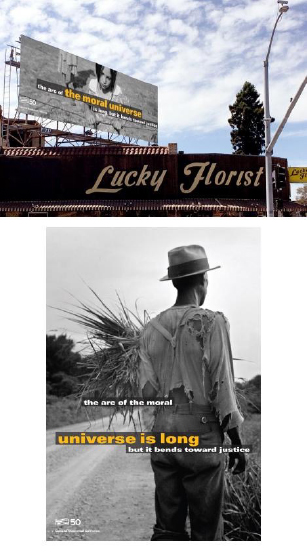

Top- A Question of Faith Billboard, Oakland, California Below: A Question of Faith Bus Shelter, Oakland/San Francisco, California Chris Johnson 2018

In 2018 the Oakland Museum of California commissioned me to create 4 billboard and 4 bus shelter public artworks that reflected upon faith and history. After two years of the Trump administration, I felt that these were qualities that all of us needed to remember.

To create the billboards and bus shelter images, I combined relatively unknown photographs by the acclaimed 20th century documentary photographer, Dorothea Lange, with the well-known phrase: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” coined by American Transcendentalist Theodore Parker in 1853 and famously referenced ever since.

Art Place, Creative Placemaking, Video Documentation

2019-2021

|

Top- Creative Placemaking Documentation image: Chris Johnson 2018, Anchorage, Alaska

Center- Creative Placemaking Documentation image: Chris Johnson 2018, Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico

Bottom - Creative Placemaking Documentation image: Chris Johnson 2018, Jackson Mississippi

In 2019 PolicyLink, an Oakland based social activist organization, commissioned me to develop a creative documentation video project about the work of the six organizations across the country who were experimenting with the process of combining traditional community development with the work of local artists in new and integral ways. This process is called Creative Placemaking.

I decided to base my video interviews on the degree to which this work was personally meaningful to all involved including staff, volunteers, residents, and community leaders. Over two years I traveled twice to each of the community development sites and interviewed dozens of individuals for the website created for this project.

https://www.communitydevelopment.art/strategies/creative-documentation)

Conclusion

I continue to work as a fine art photographer in my personal life but, Social Practice artworks and projects have become an essential way for me to engage with the world and work towards equity and justice for all of us.